The war on cars: how mobility is sabotaged in the name of equality

A silent revolution on four wheels

The car, once a symbol of freedom, prosperity and personal autonomy, is under sustained ideological attack. Cities are banning vehicles from their centers, narrowing roads, raising parking fees to unaffordable levels, and aggressively promoting public transport and cycling. These policies are sold to the public as “green”, “healthy”, or “urban-friendly”. But behind this language of sustainability and safety lies something more coercive: a political drive to restrict personal mobility and enforce mass compliance with centrally planned ideals.

The war on the car is not really about cleaner air or fewer traffic jams. It is about limiting independence. It reflects a broader ideological movement rooted in collectivist thinking that seeks to reduce all individuals to a manageable, immobile, and equalised mass. The aim is not to elevate anyone, but to make everyone equally powerless and dependent.

From freedom to dependency

The car as a symbol of autonomy

Owning a car has long been a milestone of personal freedom. It gives access to work, social life, travel, and family. It allows people to live outside dense city centers. It gives individuals control over their schedule and movements. Especially for working-class families and rural residents, the car was a great equaliser. It brought opportunities and dignity.

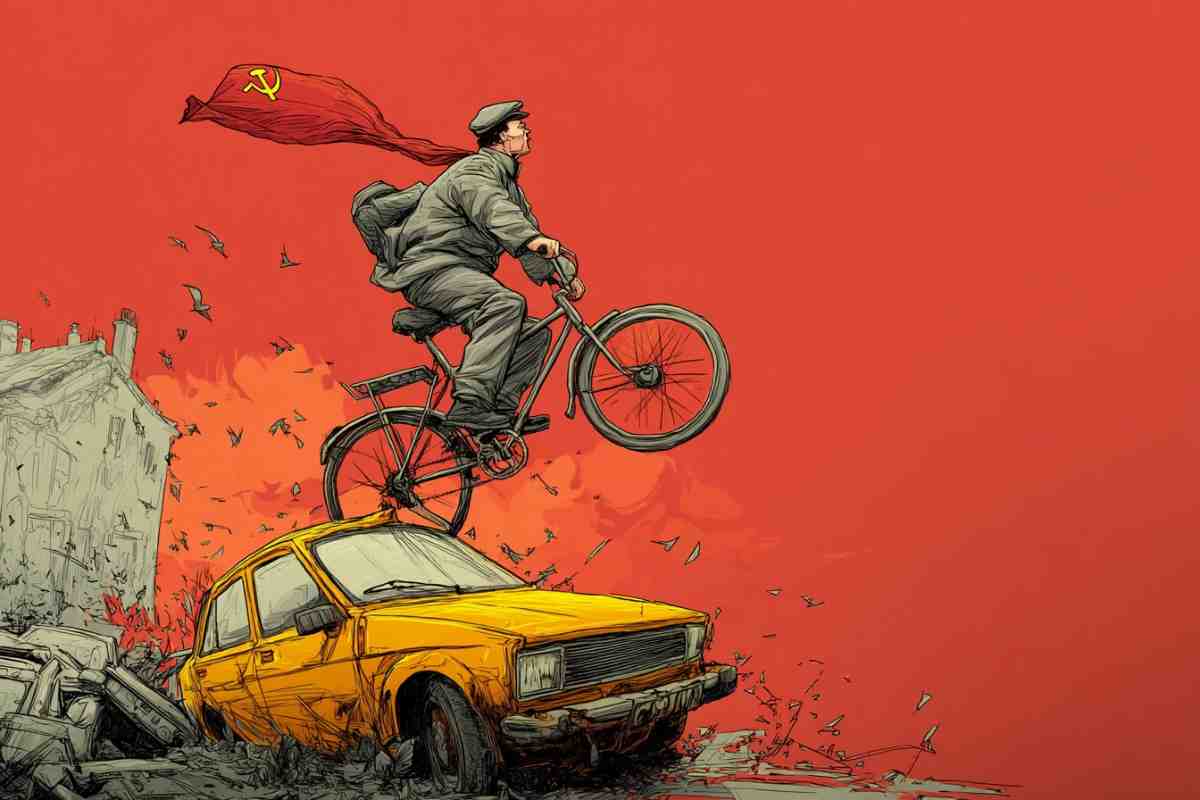

But that is precisely why cars are hated by ideologues who believe in centralised planning. Cars represent individual agency, voluntary action, and self-direction. These are qualities that collectivist regimes, from Marxist to technocratic, have always sought to suppress. A mobile population is a free population. An immobile one is easier to manage.

As James Pinkerton notes, “Mass transit is always the dream of the planner. Private vehicles are the dream of the people” (The War on Cars Is a War on the Working Class, James Pinkerton).

Climate as moral cover

Instead of honestly stating their distaste for autonomy, policymakers hide behind environmental rhetoric. Cars, they say, are dirty, dangerous, or outdated. Emission zones, congestion taxes, and parking reductions are promoted as climate measures. But even electric vehicles, hailed as the future just a decade ago, are now being targeted by restrictions, charges, and bans.

The goal is not cleaner cars, but fewer cars. In fact, policymakers increasingly argue that no one should own cars at all. The European Commission openly promotes “vehicle-free lifestyles” and “reduction of car dependency” as primary goals in its Urban Mobility Framework (European Commission, 2021).

As Václav Klaus wrote in Blue Planet in Green Shackles, “The climate movement is not about climate. It is about changing society and limiting freedom” (Blue Planet in Green Shackles, Václav Klaus).

Equality through deprivation

Green socialism in disguise

Like other social-engineering projects, anti-car policy promises equality. But it is the kind of equality familiar from communist systems: equality through shared misery. Cars are not made accessible to all. Instead, they are made inaccessible to most. The result is not mobility for the poor, but immobility for everyone.

We see this in the push for the so-called “15-minute city”, where residents are expected to live, work, and shop within their own local zones. It is presented as convenient and ecological. But in practice, it can easily become a tool of containment. London’s “Low Traffic Neighbourhoods” and “Ultra Low Emission Zones” have been used to enforce fines on residents for simply leaving their street or driving outside their district.

As journalist Ross Clark warned, “the 15-minute city is not just a planning idea. It is a mechanism of surveillance and control” (The War Against the Motorist, Ross Clark).

From transportation to compliance

Collectivist ideology always seeks to replace free access with managed access. The car stands in the way of that. It gives people too much control. That is why car ownership is now being framed as unsustainable and even immoral. In its place comes a model of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), where people must rent shared vehicles, book transport via apps, and justify every journey.

This shift reflects a broader trend in modern governance: from individual rights to conditional access. The World Economic Forum envisions cities where “nobody owns anything” and where urban travel is entirely planned and shared (Welcome to 2030: I own nothing, have no privacy, and life has never been better, Ida Auken).

In this model, movement is no longer a right, but a service controlled by digital systems. And like any service, it can be turned off.

The bicycle as an ideological weapon

A new moral hierarchy

Cycling is portrayed as virtuous and clean, while driving is portrayed as selfish and polluting. This framing sets up a moral hierarchy, used by planners to justify aggressive interventions in urban life. Bike lanes are expanded without democratic debate. Car lanes are narrowed or removed. Entire neighborhoods are restructured around non-motorised transport.

This is not just about traffic. It is about values. Cyclists are presented as modern, progressive and healthy. Drivers are cast as backward and antisocial. The result is an artificial conflict between citizens, which distracts from the real agenda: top-down control of movement.

As Ben Pile writes, “The war on the car is not a war on pollution. It is a war on choice” (The War on Cars Is Ideological, Ben Pile).

The myth of the livable city

Urban designers speak endlessly of “livability”, but what they mean is submission. A city without cars is not automatically cleaner or safer. In many cases, businesses close, elderly people are cut off from essential services, and night-time safety deteriorates.

Public transport systems, meanwhile, are underfunded, overcrowded, and unreliable. But that does not stop governments from forcing more people onto them. The idea is not to improve mobility, but to redefine it. In this model, staying local is seen as virtuous. Travelling is framed as selfish.

Supranational enforcement

The EU and UN agenda

Car-restrictive policies are increasingly dictated not by local populations, but by global institutions. The European Union, through its Green Deal and Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans, imposes targets and frameworks on member states that drastically reduce private car use.

The UN, too, promotes a vision of city life where all transport is shared, centralised, and carbon-scored. Its Agenda 2030 explicitly aims to “reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities” by controlling mobility patterns (UN Sustainable Development Goal 11).

These are not recommendations. Through funding, regulations, and legal threats, these bodies compel local governments to comply. The car is redefined not as a right, but as a problem to be phased out.

As author Patrick Wood explains in Technocracy Rising, “Technocratic governance does not tolerate personal liberty. It designs systems that demand submission” (Technocracy Rising, Patrick Wood).

Corporate collusion

Multinational corporations are not resisting this shift. They are partnering with governments to create a post-ownership transport model. Car companies are investing in subscription-based vehicles. Tech companies are developing surveillance tools, driver profiles, and vehicle-tracking systems.

Electric vehicles, though marketed as liberating, are increasingly tied to digital infrastructure that allows central control. Most can be tracked, updated remotely, or even disabled. This raises the alarming possibility of political or financial exclusion from mobility, as is already happening in China’s social credit system.

In this future, movement becomes a conditional service. The car becomes another node in a digital cage.

The return of aristocracy

Mobility for the few

In the name of equity, mobility is being withdrawn from the many. Yet elites continue to drive. Politicians use taxpayer-funded electric cars. Influencers fly from city to city to promote “green” messages. Climate conferences are filled with private jets and luxury vehicles.

Meanwhile, ordinary citizens are told to walk, bike, or pay fines. Rural families, tradespeople, and the disabled are hardest hit. Their independence is framed as unsustainable. Their needs are ignored.

What emerges is a new class divide. Those with resources and connections enjoy flexible, safe transport. The rest must adapt to constraints. Once again, mobility becomes a luxury for the few.

Manufactured conflict

To enforce this shift, governments rely on division. Motorists are demonised. Cyclists are praised. Protesters are branded extremists. Citizens are encouraged to resent each other instead of questioning the ideology behind the policies.

This tactic ensures that resistance is scattered and emotional, rather than unified and strategic. It is a classic application of “divide and conquer”, splitting society into warring factions while the central agenda advances.

As George Orwell warned, “The real division is between those who want people to be free, and those who want them to be controlled” (Collected Essays, George Orwell).

From license plate to QR code

Total mobility control

The end goal of these policies is a fully monitored mobility system. Cameras scan license plates. Cars are connected to cloud servers. Carbon limits are tracked. Movement is logged and analyzed.

In cities like Oxford and Milan, plans already exist to restrict travel based on zones and time schedules. Drivers who move too far or too often face automatic fines. This is not climate policy. It is behavioural engineering.

Combined with digital currencies and central bank control, the car of the future becomes not a tool of liberation, but an instrument of containment. Travel is allowed only when and how the system permits.

As Ayn Rand warned in Atlas Shrugged, “When the state owns your ability to move, it owns you” (Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand).

Conclusion

The war on cars is not a technical debate. It is a civilisational one. Under the language of climate and health, powerful interests are dismantling personal freedom, class mobility, and individual independence. The goal is not a cleaner world. The goal is a more manageable one.

The car represents something far greater than transport. It is a symbol of liberty, self-reliance, and escape from central control. That is why it must be defended. The battle for mobility is the battle for freedom itself.