The real impact of asylum seekers: why the “small part” narrative distorts the true picture of migration

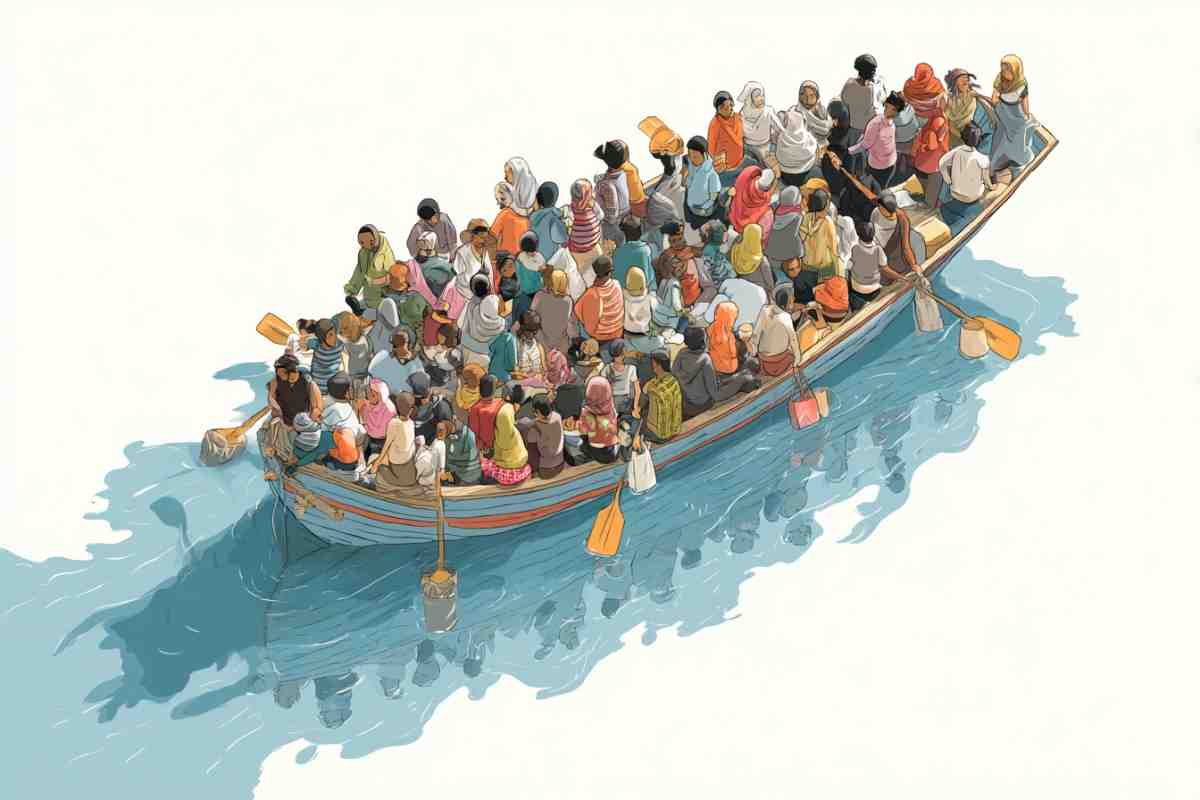

It is often repeated in political discourse and media reporting that asylum seekers form only a small fraction of total migration flows, frequently stated as around ten percent. This statistic is presented to downplay concerns about refugee migration, suggesting that asylum seekers are a minor element in the broader and more complex landscape of migration. However, this narrative is deeply misleading. It obscures the realities of how asylum migration differs fundamentally from other types of migration in terms of permanence, economic effects, social integration, and demographic consequences.

Focusing on short-term arrival numbers, which produce the “small part” figure, fails to capture the long-term and cumulative effects of asylum migration. It shows that the majority of asylum seekers do not simply come and go. Instead, they tend to settle permanently, depend heavily on social support systems, and bring demographic changes that have profound and lasting impacts on host societies.

The illusion of a “small part”: inflows versus stocks

Why the 10 percent figure is misleading

The claim that asylum seekers constitute only about ten percent of total migration is based on inflow data for a given year. It counts newly registered migrants arriving with asylum claims alongside economic migrants, students, family reunifications, seasonal workers, and intra-EU mobility. The problem is that not all migration categories behave the same over time. Temporary migrants often stay for a limited period and then leave, reducing their presence in the overall migrant population. Asylum seekers, once granted refugee status or subsidiary protection, usually remain indefinitely.

The 10 percent figure only captures the initial influx of asylum seekers. It does not account for the fact that asylum migrants accumulate year after year in the host country’s population, while many other migrants depart after their temporary stay ends. Thus, the percentage of asylum-based migrants in the stock of the migrant population is much higher than inflow data suggest.

Stocks of migrants show a different picture

For example, Eurostat data demonstrate that while economic migrants from within the European Union often move back and forth and may stay only a few years, refugees tend to remain permanently once accepted. This results in a growing proportion of refugees within the total foreign-born population over time.

The OECD’s International Migration Outlook reports that return rates for asylum seekers rejected or accepted are significantly lower than for other migrants. In many European countries, less than 30 percent of rejected asylum seekers actually return to their home countries, and accepted refugees have virtually zero return rates (International Migration Outlook 2023, OECD).

Therefore, the seemingly minor annual share of asylum seekers translates into a much more substantial and permanent demographic presence.

Permanent settlement leads to long-term consequences

Economic integration and employment challenges

Unlike many economic migrants who come with job contracts or study plans and then return home, refugees often arrive with few marketable skills, limited language abilities, and trauma from conflict or displacement. Their labor market integration is generally slow and problematic.

A comprehensive German study, the IAB-BAMF-SOEP-Befragung von Geflüchteten (2022), tracked refugees over several years and found that even after seven years only about 50 percent had found stable employment. Most worked in low-skill jobs, often below their qualifications.

Similarly, research from Sweden’s Statistiska centralbyrån (SCB) confirms that refugees have the lowest employment rates among migrant groups even after a decade, frequently relying on social welfare (Integration, en beskrivning av läget i Sverige, 2021).

Fiscal costs and welfare dependency

Multiple fiscal studies show that the net fiscal impact of asylum seekers and refugees tends to be negative for host countries over long periods. The Frisch Centre in Norway published a report in 2021 indicating that the lifetime fiscal contribution of non-European refugees is often negative by several hundred thousand euros per person (Economics of Migration and Refugees, Frisch Centre, 2021).

In Denmark, the Ministry of Finance’s 2018 report (Indvandreres nettobidrag til de offentlige finanser) estimated the annual net fiscal cost of non-Western migrants at over 33 billion Danish kroner, primarily driven by refugees and family reunifications. Similar patterns emerge in Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands, where refugee-origin migrants disproportionately rely on public benefits.

These fiscal burdens are exacerbated by the higher social and healthcare needs of refugee populations, including trauma-related mental health care and housing subsidies.

Family reunification multiplies the refugee population

The initial asylum seeker inflow is only one part of the story. Once refugees are granted protection status, they typically become eligible to bring family members through reunification policies. This legal avenue dramatically increases migration numbers linked to asylum claims.

In Germany, family reunifications following the 2015 migrant crisis added more than 100, 000 arrivals annually for several years (Migrationsbericht 2019, BAMF). Many of these new arrivals do not apply as asylum seekers but join established refugee families. This multiplier effect is often overlooked in public debates that focus narrowly on first-time asylum applications.

Because family reunifications are permanent and open-ended, they intensify the demographic and social impact of asylum migration far beyond initial inflow statistics.

Demographic and social effects of asylum migration

Concentration in urban centers and schools

Refugee-origin populations tend to cluster in specific urban areas, often in subsidized housing projects or social hotspots. This spatial concentration amplifies social segregation and challenges integration efforts.

In Sweden, the Demografiska rapporten by Statistics Sweden documented that in cities like Malmö, children with immigrant backgrounds, many descendants of refugees, already constitute the majority in primary schools (Demografiska rapporten, Statistics Sweden, 2022). Similar demographic shifts are occurring in neighborhoods across major European cities such as Amsterdam, Brussels, Berlin, and Paris.

This demographic reality shapes the character of local schools, social services, and community relations for decades to come.

Parallel societies and integration failure

Long-term settlement without successful social integration often leads to the development of parallel societies. Language barriers, cultural differences, and religious practices reinforce social enclaves.

Numerous studies reveal that refugee populations frequently maintain distinct cultural identities and social networks that limit interaction with wider society. In some cases, this leads to conflicts over norms and values.

The European Commission’s Special Eurobarometer 493 (2019) found widespread public concern about social cohesion and integration challenges, with many Europeans perceiving immigrant communities as isolated.

Security concerns and crime statistics

While it is critical to avoid stereotyping, official crime statistics in several countries show that asylum seekers and their descendants can be overrepresented in specific types of crime, including violent crime and gang-related offenses.

For example, the German Federal Criminal Police Office (Bundeskriminalamt) reported in 2018 that asylum seekers were disproportionately represented in crime statistics relative to their population size, particularly in categories such as theft, violent crime, and sexual offenses (Kriminalstatistik 2018, BKA).

Such statistics fuel social tensions and skepticism about asylum policies among the host population.

Economic migrants versus refugees: key differences

Temporary versus permanent migration

Economic migrants, including intra-EU workers, international students, and seasonal laborers, often plan to stay only temporarily. Many return to their countries of origin after finishing work contracts or education. This temporary pattern means that economic migration flows are often cyclical and do not permanently alter the demographic composition.

In contrast, asylum seekers who receive protection tend to stay indefinitely. This fundamental difference makes comparing asylum inflows to overall migration inflows misleading.

Contributions to the labor market

Economic migrants often fill labor shortages and contribute actively to host economies. Many are young, skilled, or motivated workers who pay taxes and help sustain social welfare systems.

Refugees, however, frequently struggle to enter formal employment, at least initially. Language difficulties, trauma, lack of qualifications, and social exclusion reduce their labor market participation rates. This difference affects the net fiscal and economic impact of these two groups.

Why policies continue to underestimate asylum migration’s impact

Political narratives and media framing

The persistent use of the “asylum seekers are only 10 percent of migration” figure serves political agendas that seek to minimize public concern about refugee migration. By emphasizing low inflow percentages, governments and advocacy groups create a false sense of manageability.

This framing distracts from the real issues of integration, fiscal costs, social cohesion, and demographic change that emerge only over the long term.

Lack of holistic data and analysis

Migration data often focus on arrivals rather than long-term residency and social outcomes. Governments do not always track the full lifecycle of refugees in their countries, making it difficult to assess cumulative effects.

Comprehensive longitudinal studies and transparent reporting on employment, welfare use, educational attainment, and crime rates by refugee-origin populations are necessary for informed policy making.

Conclusion

The claim that asylum seekers represent a small fraction of total migration inflows is a superficial and misleading statistic. It ignores the fundamental differences between types of migration in terms of permanence, social impact, and economic integration.

Refugee migration results in permanent settlement, high welfare dependency, family reunifications that multiply population growth, and significant demographic shifts concentrated in urban areas. These realities translate into a much larger and more lasting impact on host societies than the 10 percent figure suggests.

Sound migration policy requires moving beyond inflow numbers and examining the long-term effects of asylum migration honestly and comprehensively. Only then can societies address integration challenges, fiscal sustainability, and social cohesion effectively.

References

- International Migration Outlook 2023, OECD

- IAB-BAMF-SOEP-Befragung von Geflüchteten, Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB), 2022

- Integration – en beskrivning av läget i Sverige, Statistiska centralbyrån (SCB), 2021

- Economics of Migration and Refugees, Frisch Centre, 2021

- Indvandreres nettobidrag til de offentlige finanser, Danish Ministry of Finance, 2018

- Migrationsbericht 2019, Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF)

- Demografiska rapporten, Statistics Sweden, 2022

- Special Eurobarometer 493, European Commission, 2019

- Kriminalstatistik 2018, Bundeskriminalamt (BKA)