The illusion of inheritance tax: why it serves only the state and the ultra-rich

A tax built on envy, not fairness

Inheritance tax is presented as a tool for fairness. Politicians claim it prevents dynasties of wealth, ensures everyone contributes, and promotes equality. The rhetoric is powerful because it appeals to envy and a sense of justice.

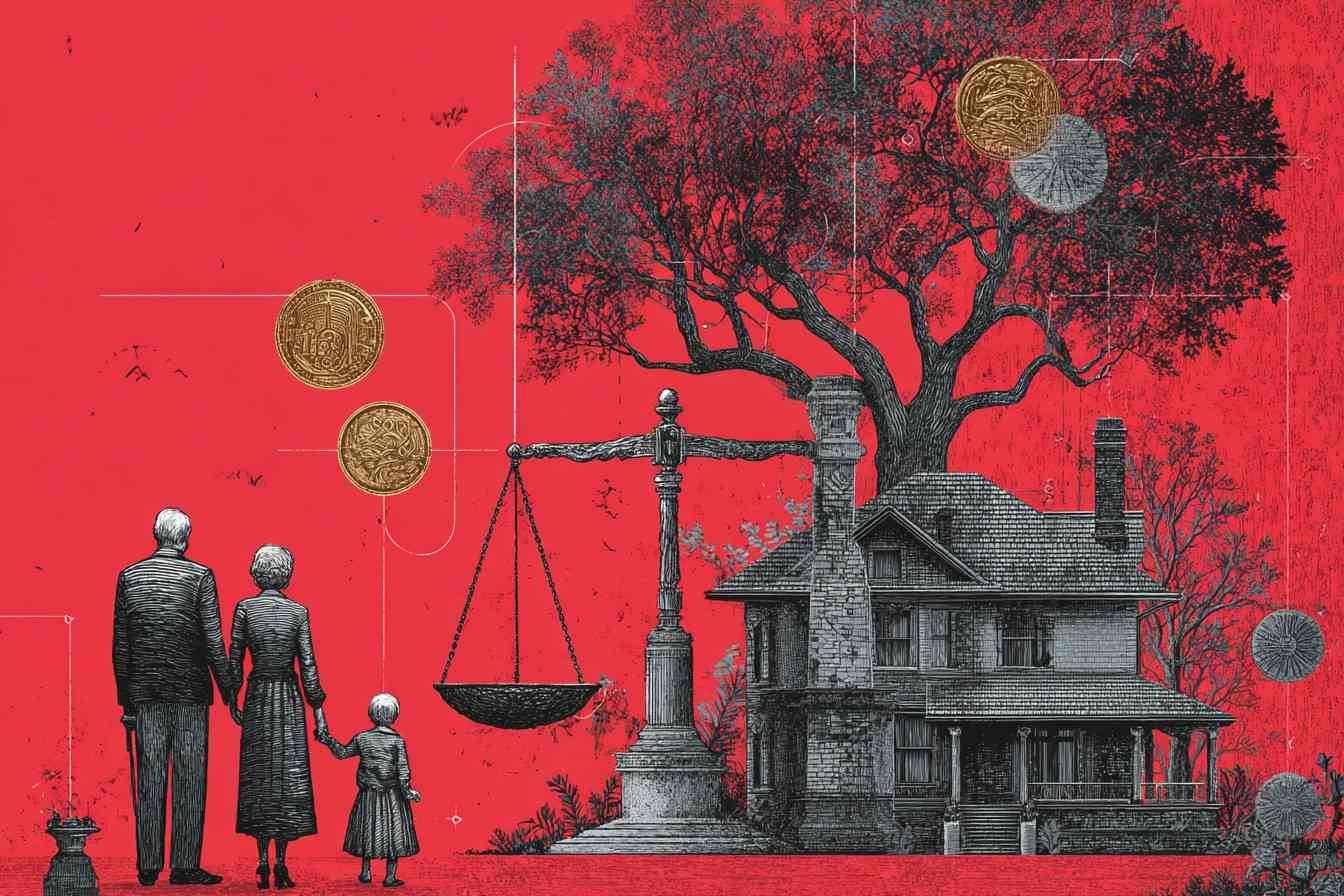

But in practice, inheritance tax does not dismantle entrenched privilege at the top. It dismantles the wealth and stability of middle- and upper-middle-class families, the very groups who invest in businesses, create jobs, and sustain communities. Meanwhile, the true elite, the top one percent, remain untouched thanks to international legal loopholes and tax havens (Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty).

The tax serves only one master: the state. It is less about fairness, more about revenue extraction and control.

How inheritance tax dismantles the productive classes

Middle- and higher-income families typically build wealth through decades of effort: running businesses, farms, shops, and professional practices. Their wealth is tied to productive assets, not idle speculation. These businesses employ people, generate innovation, and sustain communities.

When inheritance tax hits, heirs are forced to sell parts of the business, borrow heavily, or in many cases liquidate the entire enterprise to pay the state. This erodes intergenerational continuity and destabilizes local economies.

Research by the European Family Businesses federation shows that one in three family businesses cannot survive succession when inheritance tax applies (European Family Business Barometer, European Family Businesses). Instead of passing into the hands of the next generation, many are sold to multinationals or dissolved altogether. Jobs vanish, knowledge is lost, and capital concentration deepens.

Far from reducing inequality, inheritance tax accelerates the erosion of the middle class.

Historical examples of destruction

Britain’s “death duties” and the collapse of estates

Post-war Britain provides one of the clearest examples of how inheritance tax, then known as “death duties, ” destroyed productive assets and cultural heritage without ever touching the entrenched elite. At its peak in the mid-20th century, the effective rate of inheritance tax on large estates reached as high as 80 percent (Death Duties and their Consequences, David Cannadine). Families that had owned land, businesses, and cultural landmarks for centuries were suddenly unable to keep them.

The effects were catastrophic. Between 1945 and 1975, historians estimate that more than 1, 200 country houses were demolished (The Destruction of the Country House, Marcus Binney). These were not idle symbols of wealth, but estates that provided jobs, farming income, craftsmanship, and tourism. Many of them also held irreplaceable art collections, libraries, and historical archives. In numerous cases, priceless collections were sold abroad to cover tax bills, dispersing Britain’s cultural memory across the world.

Examples are abundant. The demolition of Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire, once home to the Rothschild family, was directly linked to the crushing inheritance taxes that heirs could not pay (The Rothschilds: A Family Portrait, Frederic Morton). Witley Court, once one of the grandest houses in England, fell into ruin after being sold off under tax pressure (Lost Houses of England, Giles Worsley). Even estates that survived often did so only by selling vast portions of their land or transferring entire art collections to the state in lieu of tax. The National Trust grew rapidly in these decades not because of voluntary philanthropy, but because families were forced to surrender their ancestral homes to avoid financial collapse (The National Trust: The First Hundred Years, Merlin Waterson).

This wave of destruction was not confined to aristocracy. Smaller landowners, farmers, and business families were equally hit. A farm or workshop that had been successfully run for generations could not be handed down without liquidation or heavy borrowing. For many heirs, the inheritance tax bill exceeded the cash value of the assets themselves, leading to forced sales at below-market prices. The buyers were usually larger corporations or wealthy investors who had the means to absorb the cost, deepening concentration of ownership.

Far from redistributing wealth, Britain’s death duties reshaped society in the opposite way: they weakened the productive and cultural middle layers of the nation while doing nothing to curtail the power of entrenched elites. Those who had access to offshore structures or legal constructs kept their fortunes intact. The destruction fell instead on families whose wealth was tied up in tangible assets within the country, where the state could reach them.

France’s burden on small enterprises

France has some of the heaviest inheritance taxes in Europe. Rates can reach 45 percent for direct descendants and much higher for distant relatives (Impôt sur les successions: un frein pour l’économie, Institut Montaigne). A study by the Institut Montaigne showed that over 60 percent of French small business heirs considered selling their firms rather than taking on tax debt.

This environment discourages entrepreneurship and accelerates the sale of companies to global conglomerates. The supposed goal of equality is undermined by the loss of national economic independence.

The United States and the survival of dynasties

The U.S. estate tax, often defended as a progressive measure, currently applies only above $12.9 million per individual (IRS, 2023 threshold). Yet the ultra-rich avoid it easily. Dynasty trusts, foundations, and offshore accounts ensure that vast fortunes like those of the Rockefellers and Waltons remain intact (Wealth and Inequality in America, Jeffrey Winters).

Meanwhile, family-owned farms and businesses just above the exemption threshold are forced into liquidation or debt. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office has repeatedly noted that administrative and legal avoidance schemes reduce the effective estate tax rate for billionaires to near zero (The Estate Tax and Its Burden, Congressional Budget Office). The tax harms only those just below the billionaire class.

The myth of equality through taxation

Governments argue that inheritance tax reduces inequality. But the numbers expose the illusion.

According to the OECD Revenue Statistics (2022), inheritance and estate taxes account for less than 0.5 percent of total tax revenue on average across member states (OECD Revenue Statistics 2022, OECD). In some countries, it is barely measurable.

Here is a comparison of selected countries:

| Country | Inheritance/Estate tax revenue (% of total tax revenue) |

|---|---|

| Germany | ~0.2% |

| Netherlands | ~0.6% |

| France | ~1.3% |

| United Kingdom | ~0.7% |

| United States | ~0.3% |

| OECD average | ~0.5% |

For such a negligible contribution, the social and economic cost is immense. Family firms close, communities weaken, and intergenerational stability is destroyed.

Meanwhile, the top one percent escape entirely, using trusts and cross-border wealth transfers. True inequality, the one between billionaires and the rest of society, is never addressed. Instead, the state diverts public anger toward the modestly wealthy while the truly powerful are untouchable.

The untouchable elites and their schemes

The global elite does not worry about inheritance tax. Their wealth is structured to avoid it.

- Trusts in jurisdictions like Jersey, Bermuda, or Delaware separate legal ownership from beneficiaries, meaning no “inheritance event” occurs.

- Foundations in Switzerland or Liechtenstein provide indefinite preservation of assets.

- Holding companies in Luxembourg, Singapore, or the Cayman Islands disguise true ownership.

- Philanthropic vehicles like charitable foundations allow billionaires to move wealth out of their personal estates while still controlling it (Secrecy World, Jake Bernstein).

These mechanisms cost money, but for billionaires, the expense is trivial compared to the billions preserved. The ultra-rich pay almost nothing, while ordinary families with businesses, farms, or modest portfolios are squeezed.

Inheritance tax thus reinforces inequality by protecting dynasties while dismantling the middle.

The historical role of inheritance tax

Inheritance tax was not created to promote fairness. Its origins lie in state expansion and revenue hunger.

- In Britain, the first modern inheritance taxes were introduced in the late 19th century to fund wars and rising public spending (Death Duties in the British Tax System, Martin Daunton).

- In the United States, the estate tax was introduced in 1916, explicitly as a wartime measure (A History of Federal Estate and Gift Taxes, Internal Revenue Service).

- Across Europe, inheritance taxes expanded after World War II to finance welfare states (Public Finance in Democracies, Richard Musgrave).

Always the justification was “fairness, ” but the real motive was government revenue. Even today, despite the negligible sums raised, governments refuse to abolish inheritance taxes because they fear losing even this sliver of income.

The truth is that inheritance tax is a symbolic weapon. Its purpose is not to fund the state efficiently, but to signal moral superiority and to maintain political control.

Innovation and job creation suffer

Family businesses employ a massive share of the workforce. In the European Union, over 60 percent of private sector jobs are provided by family-owned companies (Family Business Statistics in Europe, European Commission). In the United States, family firms employ 62 percent of workers and create 78 percent of new jobs (Family Business Facts, Conway Center for Family Business).

Inheritance tax destabilizes this foundation. When heirs must sell companies or take on debt to pay taxes, growth halts. Innovation requires stability and long-term planning, not short-term asset liquidation.

By undermining the survival of family enterprises, inheritance tax damages the very engine of prosperity. Jobs are lost, productivity declines, and multinational corporations gain ground at the expense of local communities.

Government hypocrisy and greed

Governments use moralistic rhetoric to justify inheritance tax. They call it a tool for fairness and opportunity. But the numbers reveal the hypocrisy.

- Inheritance taxes raise less than one percent of state revenues in almost every developed country (OECD Revenue Statistics 2022, OECD).

- Administrative costs, avoidance schemes, and distortions often consume a large part of what is collected (The Economics of Inheritance Taxation, Richard Bird).

- The real inequality — the gap between the ultra-rich and the rest — is never touched (Global Wealth Inequality, Branko Milanovic).

Instead, inheritance tax serves to weaken those who cannot fight back. Politicians enjoy the theater of fairness while ensuring their allies among the billionaire class remain safe.

The hypocrisy is glaring: governments claim to attack inequality while actively preserving it.

The real inequality: the one percent versus the rest

The global top one percent controls over 45 percent of wealth worldwide (Global Wealth Report 2023, Credit Suisse). The bottom half of humanity owns barely one percent. This is the real inequality, a chasm so vast it defies historical precedent.

Inheritance tax does nothing to change this. The ultra-rich avoid it entirely. The victims are the middle and upper-middle classes, the business owners, professionals, and savers who cannot hide their wealth abroad.

By taxing them, governments erode the only counterbalance to oligarchic dominance. Citizens are told to resent a neighbor inheriting €500, 000 while ignoring billionaires shifting tens of billions offshore. Inheritance tax thus functions as political misdirection.

A call for genuine equality

If states were truly committed to equality, they would target the structures that allow wealth to escape taxation. They would dismantle secrecy jurisdictions, regulate trusts, and expose the mechanisms of offshore finance. But such measures are never taken, because the political class is deeply entangled with the global elite.

Instead, inheritance tax continues to be used as a symbolic gesture, punishing the wrong people while leaving systemic inequality untouched.

True equality would mean allowing families to preserve and expand their wealth, strengthening the productive classes that generate jobs and innovation. It would mean breaking the untouchable structures of the one percent, not destroying the modest gains of those below them.

Conclusion: a system of theft disguised as fairness

Inheritance tax contributes almost nothing to government budgets, yet its social and economic damage is immense. It destroys family businesses, weakens communities, and entrenches inequality by sparing the one percent.

Far from creating fairness, it creates dependence. Far from being progressive, it is regressive. It dismantles the middle while protecting the top.

Inheritance tax is theft masquerading as justice, a tool of state greed disguised in moral language. Until society recognizes this, the state will continue to loot the productive classes, while the truly powerful remain untouched and unbroken.