Manufactured fear, invisible crises, and the quiet machinery of control

The architecture of fear

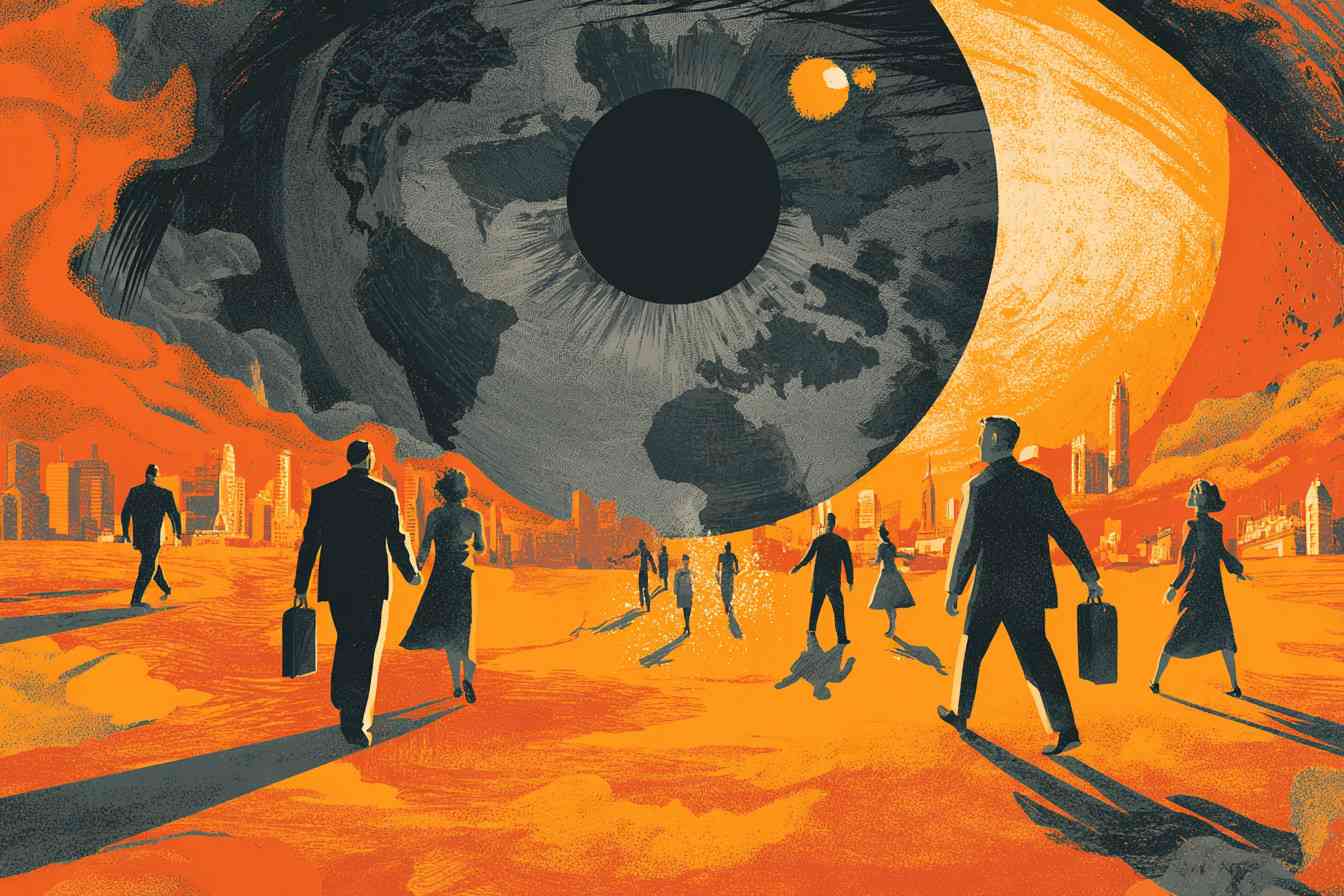

Modern states present themselves as guardians of stability, protectors against uncertainty, and caretakers of public wellbeing. Governments adopt the language of safety, security, resilience and collective responsibility. Yet behind this vocabulary lies a persistent pattern in which institutions exaggerate, construct or manipulate perceptions of crisis in order to shape public behaviour. Fear becomes a tool, a resource, sometimes even a commodity. Whether the subject is security, health, climate, migration or economics, governments often operate less as servants of the people and more as managers of public emotion.

Power is maintained not simply through laws, taxes or institutions, but through psychological leverage. Fear changes the way populations think, how they vote, how they consume news, and how they relate to authority. A frightened population seeks protection, and governments are eager to present themselves as the only legitimate source of that protection. It becomes a circular dynamic in which institutions define the threat, amplify the threat, and then offer themselves as the antidote.

The idea that fear can be politically useful is not new. Historical scholars have traced its use back to ancient empires and medieval monarchies. Yet its modern form is more refined, more subtle, and often cloaked in administrative language. Contemporary fear rarely arrives as outright terror. Instead it appears as rolling crises, constant alerts, emergency narratives, and a sense that society is permanently on the edge of something catastrophic. The result is a public mood that oscillates between uncertainty and dependence.

Crisis as a political instrument

The cycle of fear creation

Governments rarely need to invent a crisis entirely. More commonly, they take an existing problem, exaggerate its magnitude, simplify its causes, and then frame it as a threat that can only be addressed through sweeping powers. Public fear is amplified through repetition, symbolic imagery and the language of inevitability. Once fear takes hold, even temporary measures can become permanent.

Political theorist Corey Robin has written extensively on the use of fear in political systems. In Fear: The History of a Political Idea (Corey Robin), he argues that fear thrives where hierarchies wish to preserve themselves. It keeps populations compliant and discourages dissent. While Robin focuses primarily on classical political theory, the same dynamics appear in modern bureaucratic states.

The architecture of fear usually follows a predictable pattern:

- Define a crisis, often vaguely, with shifting boundaries.

- Amplify uncertainty, ensuring that the public cannot fully understand the scope or causes.

- Associate the danger with everyday life, making compliance feel like moral duty.

- Propose sweeping interventions, framed as temporary, technical or necessary.

- Normalize the new powers, even after the crisis subsides.

Governments rarely reverse their expansions of power. Emergency laws stay in place. Surveillance tools remain active. Institutions grow accustomed to greater discretion, fewer checks and broader authority.

Manufactured urgency and artificial consensus

Most citizens cannot verify large scale claims about security, health, climate or economics. Much of the information is too complex, too technical, or simply hidden behind classified documents and bureaucratic opacity. This enables governments and institutions to define reality for the public, turning interpretation into power.

The sociologist Ulrich Beck describes this phenomenon in Risikogesellschaft (Ulrich Beck). Beck argues that modern societies become risk oriented, meaning institutions perpetually identify potential catastrophes in order to justify their relevance. Even when the intention is benign, the outcome is similar. Fear becomes structural.

Institutions do not merely react to crises, they cultivate the conditions under which crises appear indispensable. As long as the public perceives fragility, the state remains necessary.

The psychological dimension of control

Fear changes cognition

Fear narrows attention. It reduces critical thinking and encourages obedience. People under chronic stress are more likely to defer to authority and less likely to challenge narratives. Psychological research has repeatedly shown that fear makes individuals susceptible to simplified explanations and more willing to trade liberties for reassurance.

The political use of fear is therefore effective precisely because it transforms the mental environment of a population. When people believe danger is near, they become more isolated, more anxious, and more dependent on expert guidance. A fearful population loses its sense of agency.

In The Politics of Crisis Management (Arjen Boin and Paul t Hart), the authors note that governments often use fear not only to maintain order, but to manage public expectations. Crises create opportunities for leaders to appear decisive, competent and irreplaceable. They also distract from systemic failures that occur outside moments of emergency.

The feedback loop between media and institutions

Media plays a central role in amplifying fear. Although many outlets claim independence, most rely heavily on government data, government experts and government framing. Crises make good headlines and good business. They create urgency, engagement and political polarization.

This synergy produces a feedback loop:

- institutions declare danger

- media broadcasts it with dramatic emphasis

- the public reacts with anxiety

- institutions respond by demanding more power

- media repeats the cycle with new angles

As Noam Chomsky outlines in Manufacturing Consent (Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman), media often functions less as a watchdog and more as a conveyor belt for institutional narratives. While the work focuses on economic and political pressures, the same logic applies to crisis narratives.

Government officials rarely correct exaggerated reporting. Fear serves them well. It discourages scrutiny and directs public anger away from structural problems toward symbolic threats.

The mechanics of crisis inflation

Vague metrics and shifting definitions

One of the most common tactics in crisis inflation is the use of metrics that are opaque or constantly redefined. Key terms like safety, resilience, security, extremism, misinformation and threat often lack stable definitions. This ambiguity allows governments to adjust the narrative as needed.

This tactic also enables institutions to present any undesirable trend as part of a larger emergency. When an issue is described as a threat to national stability or global safety, dissenting opinions are reframed as irresponsible or dangerous.

Selective data and expert monopolies

Governments often rely on closed panels of experts who reinforce institutional agendas. These experts may be credible in their fields, yet their selection is political. Less convenient voices are excluded.

The economist Mariana Mazzucato highlights this in The Value of Everything (Mariana Mazzucato), noting that institutions often elevate experts who align with their preferred narrative. While the book focuses primarily on economics, the principle applies broadly. When only one type of expert is granted legitimacy, crisis interpretation becomes monopolized.

Fear as distraction from structural decline

Fear based governance diverts public attention from issues that are long term, complex and politically inconvenient. Economic stagnation, declining trust, demographic shifts, institutional corruption, and failing public services are pushed aside when populations are inundated with fears of external or abstract threats.

Political scientist Jan Werner Müller discusses this dynamic in Was ist Populismus (Jan Werner Müller), explaining how governments use crisis narratives to mask governance failures. Although Müller focuses on populism, the underlying pattern is visible across political systems.

Why governments do not have the public’s interests at heart

Institutional self preservation

Governments often present themselves as altruistic, yet institutions behave like organisms. Their primary instinct is self preservation. Bureaucracies grow, protect their budgets, avoid accountability and resist oversight. Leaders prioritize political survival, not public wellbeing.

Even democratic systems are vulnerable. Elections may change faces, but the underlying machinery of ministries, agencies and advisory councils remains intact. These institutions often shape policies more than elected officials, and they operate with minimal public scrutiny.

Conflicts of interest and power consolidation

Many modern crises enrich or empower specific groups: corporations, security agencies, international organizations, political parties and administrative elites. Fear enables policies that would otherwise face opposition.

Examples include:

- increased surveillance powers

- expanded censorship authorities

- larger budgets for security agencies

- emergency procurement contracts

- limitations on public assembly

- centralization of decision making

These measures frequently outlast the crises that justified them.

The erosion of accountability

Fear provides convenient cover for failure. Leaders can claim that circumstances were unprecedented or that decisions were made under pressure. Investigations are postponed, documents withheld, and mistakes reframed as necessary sacrifices.

In Crisis and Leviathan (Robert Higgs), the economist argues that governments consistently expand during crises and then retain much of their new power afterward. Although the book focuses primarily on the United States, the mechanism is universal.

Public interest as a rhetorical tool

Governments often claim to act for the greater good. Yet this phrase usually serves as a moral shield rather than a genuine objective. The public interest is invoked to justify actions that limit transparency or curtail dissent. When institutions claim to be acting for everyone, they often avoid specifying who benefits and who pays the cost.

In reality, the state frequently prioritizes:

- political stability

- economic control

- institutional credibility

- international alliances

- administrative convenience

These priorities rarely align perfectly with the interests of citizens.

Fear as a global governance strategy

International organizations and crisis narratives

Global institutions such as the United Nations, the World Health Organization and various transnational bodies use crisis framing to maintain relevance. They often describe global challenges in apocalyptic terms, portraying themselves as indispensable coordinators of the future.

This internationalization of fear adds layers of authority. National governments can deflect responsibility onto global bodies, while global bodies rely on national governments to enforce their mandates. Crisis becomes transnational, and accountability becomes diffuse.

The historian Philip Bobbitt describes this dynamic in The Shield of Achilles (Philip Bobbitt), arguing that modern states increasingly define themselves through security narratives.

Permanent emergencies and moralized politics

The concept of a permanent emergency shapes modern governance. Populations are encouraged to believe that threats are omnipresent, that solutions require constant vigilance, and that deviation from institutional guidance is reckless or immoral. This moralization of politics reduces space for debate. Those who question the narrative are portrayed as dangerous or irresponsible.

Fear thus becomes not only a political instrument but a social norm.

The human cost of fear based governance

Social fragmentation

Fear driven politics deepens divisions. When governments highlight threats from particular groups, ideas or behaviours, societies fracture. Distrust rises, cooperation declines, and citizens begin to view each other as risks. This undermines the foundation of democratic culture.

Loss of autonomy and creativity

A population conditioned by fear becomes less imaginative. Innovation, risk taking and independent thought decline. People become cautious not only about actions but about ideas. Fear narrows psychological horizons.

Emotional exhaustion

Chronic fear leads to fatigue, anxiety and despair. A society constantly told that the world is dangerous struggles to maintain optimism. This emotional exhaustion makes citizens easier to govern and less likely to resist.

Reclaiming autonomy in an era of manufactured fear

Critical thinking as resistance

The first step toward resisting fear based governance is to recognize its mechanisms. Understanding how narratives are constructed makes them less potent. Citizens who question framing, examine incentives and seek diverse sources of information are less susceptible to manipulation.

Institutional transparency

Governments should be compelled to disclose data, methodology and decision making processes. Vague claims and appeals to authority should be challenged. Transparency reduces the ability of institutions to weaponize uncertainty.

Decentralization and local agency

Power concentrated at national or supranational levels is easier to use for fear based control. Local decision making, community engagement and smaller scale governance reduce manipulation. People who participate directly in shaping their environment are less vulnerable to abstract narratives of crisis.

A culture of calm rather than alarm

Societies need cultural norms that value stability, reason and perspective. Constant alarmism corrodes public resilience. Encouraging calm responses to challenges, rather than theatrical panic, disrupts the cycle of institutional fear production.

Toward a more humane political order

Fear is an ancient human emotion, but its systematic use by modern institutions has transformed it into a tool of governance. States and organizations often claim to protect citizens, yet they rely on frightened populations to justify ever expanding authority. The result is a political landscape defined by crises that never fully resolve, emergencies that never fully end, and a public whose trust is constantly leveraged but rarely rewarded.

Breaking this cycle requires vigilance, transparency, civic courage and a refusal to accept fear as the default condition of public life. People cannot be free when they are afraid. And institutions that rely on fear do not serve the public, they manage it.