Green words, hollow core: how “sustainability” became a cult of optics

The rise of green language

In recent decades, few words have been repeated as frequently as sustainability, green, eco-friendly, and carbon neutral. These terms have penetrated everything from corporate strategies and government policies to the labels on our food and clothing. At first glance, they suggest moral virtue, environmental awareness, and responsibility for future generations. Companies flaunt them to appear progressive, while politicians use them as proof of their foresight.

Yet behind these words lies a dangerous emptiness. They are often used as instruments of persuasion rather than as clear concepts. They can mean everything and nothing at the same time precisely because there is no universally accepted definition. Sustainability originally referred to the simple principle of not depleting resources for future generations, as described in reports like Our Common Future by the World Commission on Environment and Development (Our Common Future, World Commission on Environment and Development). Today, it can just as well describe a plastic-wrapped product from a multinational as a small-scale environmental project.

The problem is not merely semantic. When words become detached from measurable reality, they are easily deployed for profit or political power. Companies use “green” language to sell overpriced products or to obscure harmful supply chains. Governments introduce new taxes and regulations under the banner of sustainable development. Protecting the environment is crucial, but these hollow buzzwords replace genuine debate and critical analysis with superficial slogans that suffocate rational thinking (Easy money trades sustainable debt market, Financial Times).

The emptiness of green slogans

A single word like sustainable can nowadays describe almost any activity, no matter how harmful or illogical it may be in practice. A luxury brand, for example, can claim that its new line of electric SUVs is “green, ” despite the enormous emissions and environmental damage caused by mining and transporting the rare metals in the batteries. Energy companies sell the illusion of carbon neutrality through so-called offset projects that supposedly “balance out” their emissions. In reality, many of these projects are nothing more than accounting tricks that deliver no tangible environmental benefit (Rise in legal challenges over carbon credit schemes, The Guardian).

Governments and companies cleverly exploit the vague and positive image of these terms. A government can call its policy sustainable simply by subsidizing wind turbines, while quietly importing coal-generated electricity from abroad. A clothing brand can boast a “green collection” made of organic cotton while its global production still relies on exploitation and water waste (Lithium robs Chilean communities of water, DW).

This hollow language is no accident. It is deliberately deployed because it allows institutions to present themselves as virtuous without making fundamental changes. It is easier to slap a green label on a product than to tackle the real problems, overconsumption, inefficient energy networks, and unsustainable urbanization (Behind the green curtain voluntary carbon market, Carbon Market Watch).

Cult and moral superiority

One of the most worrying aspects of the modern sustainability narrative is its quasi-religious character. The language of green and eco-friendly living is presented not only as a practical necessity but as a moral duty. Those who conform to the “green lifestyle” are seen as enlightened and virtuous, while skeptics or critics are dismissed as backward, selfish, or even dangerous (How the Right Is Waging War on Climate-Conscious Investing, The Atlantic).

This binary logic stifles debate. Those who question the efficiency or logic of certain “green” measures are quickly branded climate skeptics. Expressing concerns about the environmental and economic downsides of large wind farms or the waste problem of solar panels can lead to social exclusion. Serious discussions about costs, side effects, and alternatives give way to simple slogans like go green or net zero now (Rise in legal challenges over carbon credit schemes, The Guardian).

The cult-like nature of the movement is also visible in the obsession with symbolic acts. People are encouraged to separate every piece of plastic, even though most of it ends up in incinerators or foreign landfills. Electric cars are praised as climate saviors, even though emissions and pollution from their production and batteries can outweigh the benefits for years. These actions often have more to do with displaying the right attitude than actual impact (Energy Australia apologises greenwashing legal action, The Guardian).

Contradictions and harmful effects

The nuclear paradox

Few things illustrate the illogic of “green” policy as sharply as the aversion to nuclear energy. Nuclear plants emit as little CO₂ over their lifecycle as wind or solar energy (Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of energy sources, IPCC). Yet they are portrayed as dangerous and “unsustainable, ” while polluting coal and gas plants remain online to keep the grids stable. Germany shut down its nuclear plants and subsequently became more dependent on coal, leading to higher energy prices and more emissions (Germany’s nuclear shutdown mistake, Foro Nuclear).

Mining and destruction for rare metals

The “clean” image of renewable energy conceals the devastating processes required. Electric cars and solar panels demand enormous amounts of lithium, cobalt, and rare earth metals. Extracting these materials destroys ecosystems, pollutes rivers, and consumes huge amounts of water. In Chile’s Atacama Desert, lithium mining is linked to severe water shortages for indigenous communities (Mining companies pumping seawater Atacama, The Guardian). In China, rare earth mining around Baotou has caused toxic waste lakes and health problems (Rare-earth mining in China heavy cost, The Guardian).

Renewable waste mountains

Even technologies celebrated as the future of sustainability, solar panels and wind turbines, create new environmental problems. Solar panels have a limited lifespan of 20 to 30 years and often end up in landfills due to a lack of affordable recycling technologies (Solar Panel Waste Management, MDPI). Wind turbine blades, made of complex composites, are barely recyclable and are buried in large quantities (Wind turbine blades waste problem, The Conversation). These inconvenient facts are rarely mentioned in promotional materials about “green energy.”

Greenwashing and economic advantage

The success of hollow green terms is largely explained by the economic benefit they bring. For companies, words like sustainable and environmentally friendly are marketing goldmines. They can charge higher prices and attract consumers who want to feel they are doing good. Airlines sell “carbon-neutral” flights, banks offer “green” investment funds, and energy suppliers promote “renewable” contracts while their business models barely change (Behind the green curtain voluntary carbon market, Carbon Market Watch).

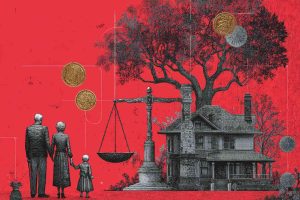

This phenomenon, known as greenwashing, has become a multi-billion-dollar industry. Governments add to this by using sustainable rhetoric to introduce new taxes, emissions trading, and stricter regulations. Under the guise of saving the planet, bureaucracies expand, wealth is redistributed, and measures are imposed that often do little for nature conservation or emission reduction. Citizens ultimately pay the bill, lose freedoms, and are left with a false sense of progress (Easy money trades sustainable debt market, Financial Times).

The triumph of emotion over reason

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the “green” movement is that emotional appeal has become more important than rational analysis. Instead of asking whether a measure truly reduces emissions or enhances biodiversity, the focus is on whether it sounds good and fits the dominant narrative. Emotional slogans like there is no planet B are used to silence rational criticism (Misleading CO₂ compensation promises air travel, Härting Rechtsanwälte).

This leads to extreme and sometimes irrational policy choices. Cities ban certain vehicles without investing in public transport. Governments mandate biofuels that require massive deforestation (Europe palm biofuel phase out dismayed, Mongabay). Companies spend fortunes on offset programs that produce monoculture plantations harmful to biodiversity. All this is justified with the vague label sustainable, even when the net effect is destructive.

Toward real environmental responsibility

Those who truly want to protect the environment must look beyond empty slogans. Real sustainability is not about slapping a green label on products or performing symbolic acts. It requires difficult conversations about choices, costs, and long-term effects. It means acknowledging that technologies like nuclear energy may be necessary, however unpopular. It also means holding companies and governments accountable for the full lifecycle of their products and policies instead of hiding behind buzzwords.

Principles for a rational approach

- Focus on outcomes, not appearances. Policies should be evaluated based on measurable reductions in emissions, waste, and resource use (Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of energy sources, IPCC).

- Reject empty labels. A product is not sustainable just because it is marketed as such; the entire chain must be considered (Behind the green curtain voluntary carbon market, Carbon Market Watch).

- Choose pragmatism over ideology. Solutions should be selected based on effectiveness and scalability, not popularity (Chapter 6: Energy systems, IPCC AR6).

- Demand transparency. Companies and governments must disclose the full environmental impact of their actions, including hidden costs (Rise in legal challenges over carbon credit schemes, The Guardian).

Conclusion: stripping away the mask

Modern terms like sustainability, green, and eco-friendly often have more in common with advertising slogans than with science or rational policymaking. These words have become incantations meant to signal virtue and suppress criticism. As long as they are not tied to concrete, measurable results, they remain tools of deception rather than means to real progress.

A truly sustainable future cannot be built on slogans. It requires honesty, rational decision-making, and the courage to break through comforting illusions. Until then, green remains primarily a color of illusion.